Keeping it real

Long dismissed as the television of television, reality TV is more culturally resonant than ever. And finally, writes Kathryn Madden, it’s in on the bit

Next time you’re at a dinner party and the conversation starts to lull, try dropping in the phrase “It’s not about the pasta” or “Lucy Lucy Apple Juicy”. Sit back and watch as the table parts like the Red Sea, dramatically dividing into two camps. One will launch into animated discussions about yachties, Mormon housewives and Hamptons share houses, connecting over tidbits that occupy a special compartment in their brains, the cerebral equivalent of a second stomach for dessert. The other group will remain silent and a little miffed; they might project an air of superiority, but they’re intrigued by this foreign lexicon.

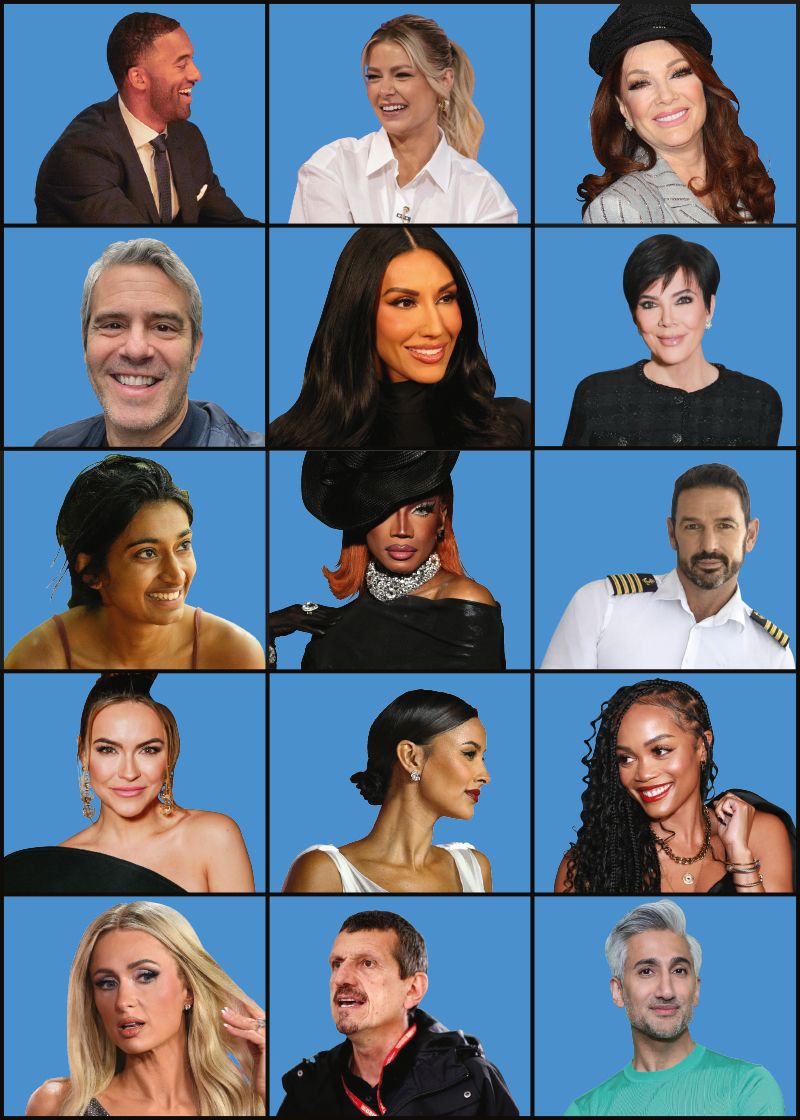

There are two types of people in the world: those who speak Bravo, and those who don’t. The former know that the American television network, which produces most of the world’s biggest reality shows including The Real Housewives franchise and Vanderpump Rules, is a pop culture phenomenon, a world unto itself affectionately dubbed the Bravoverse. The latter are more likely to consume zeitgeist-capturing comedy or ambitious HBO dramas, though even they would struggle to escape the cultural resonance of reality TV right now.

Consider this: when the Vanderpump Rules cheating fiasco known as Scandoval broke last year, so seismic was the fallout that it was covered at the White House Correspondents’ dinner (as The Cut inquired, “Does this mean Biden knows about Scandoval?”). This – for a 10-year-old reality show about a messy Los Angeles friendship group that’s garnered a cult following within the Bravo sphere but otherwise remained niche — was shocking, even, or especially, for fans. Not that the intersection of politics and reality TV was new; a role on The Apprentice accelerated the political rise of the 45th president of the United States, Donald Trump, who would come full circle and appear on Keeping Up with the Kardashians with America’s other first family in 2019. On the Golden Globes red carpet this January, friend of the Kardashians and Oscar winner Jennifer Lawrence spoke less about her latest film and more about the earth-shaking finale of The Real Housewives of Salt Lake City, which played out like a shadowy film-noir drama you couldn’t write. On that note, as Hollywood writers and actors went on strike in 2023, reality TV shifted further to the forefront – though in the wake of allegations of exploitation behind the scenes, some called for its stars to unionise too. Meanwhile, one of the year’s most-watched scripted series, Netflix’s Squid Game, was re-imagined as a reality game show with a US$4.56 million cash prize. Back to life or back to reality? Everywhere you turn, the genre is permeating culture, spinning and casting its own intricate, interconnected web.

They know WE KNOW they’re making a SHOW.

Since its earliest iterations in the ’90s, reality television has lit up the brain’s pleasure centre. Voyeurism! Aspiration! Relatability! We watched People Just Like Us on The Real World; People Just Like Us But Amplified on Big Brother; People Just Like Us But Prettier on The Hills; and a stream of top chefs, top models, teen mums, dance mums, drag queens and deck crews who invited us into their lives and made for easy, dopamine-rich viewing. “Watching an entire season of Teen Mom OG in one sitting may feel like the shameful intellectual analogue to binge eating a sleeve of cookies,” says Professor of Sociology Danielle J. Lindemann, author of True Story: What Reality TV Says About Us. “But I’m also coming at this a little on the defensive, because people say that reality’s not a valid form of entertainment. And actually, if you start drilling down into these shows, you can learn something about social life. They reveal the contours of society in an augmented, caricatured way.” As Lindemann emphasises, it’s a genre that’s dismissed as frivolous, yet it’s also been analysed ad nauseam: why do we like reality TV? What makes it a guilty pleasure? Is it real? Is it fake? Is it dumb? All valid questions, but ones that now feel tired, like a cast member of Summer House who’s been dragged out of bed before 2pm.

Back at the dinner party, there’s more to be gleaned. For one thing, guests will share that they live for Below Deck or Sister Wives with little to no shame, which might not have been the case a few years ago. This could be because Smart People Love Dumb Things now constitutes an entire #content category (even if that love is cushioned with irony), and we’re moving to embrace cringe over cool. Or maybe it’s because figures like Michelle Obama, Florence Pugh and Meryl Streep have gone public as Housewives fans. That’s the other thing about the dinner party scenario – you can’t safely predict which guests will fall into which camp. Your cousin with a PhD in Tolstoy? Addicted to Love Island. InStyle’s fashion director Rachel Wayman, an arbiter of good taste? Bravo superfan. “It’s how I wind down. A few years ago I stopped watching content that made me feel heavy; I like that reality is low stakes.”

“We view it as a PROFESSIONAL competitive SPORT."

As Hollywood screenwriters, Lizzy Pace and Chad Kultgen weren’t likely reality connoisseurs either. They met while working on NBC sitcom Bad Judge (Kultgen was a co-creator) and bonded over a shared fascination with long-running ABC dating show The Bachelor. Except for them, it’s not a dating show. “We view it as a professional competitive sport,” deadpans Kultgen. The thesis is broken down in glorious detail on the pair’s podcast Game of Roses, which sits somewhere between tongue-in cheek and deeply serious, sometimes at the same time. “Lizzy and I found that there are these repeated patterns, almost like quarters in a football game or innings in a baseball game... and we’ve carried out statistical analysis of the entire show to figure out the best strategies to win.” It makes sense: reality fans follow seasons, pick sides and gather for finales – their Super Bowl – and Game of Roses offers a scoring system, lingo and post-game analysis. It’s a framing that unconsciously rallies against sexist assumptions (sport is masculine and socially laudable; reality TV is feminine and trash), and also nods to the wider intellectualisation of the genre. The duo spent months “hyper-bingeing” and studying the show to write a book, How to Win The Bachelor, which has allegedly been smuggled onto set by contestants (‘players’) hoping to find fame and followers, ahem, everlasting love. But, more than that, it’s an invitation to watch the show in a new light, a bit like WWE wrestling, where the competitors are in on the bit.

The best reality stars today are self-aware; they know they’re making a show, and they know we know they’re making a show. It’s why little flashes that break the fourth wall are seeping into the genre, a marked shift from early reality TV where acknowledging the cameras was a cardinal sin (this makes the 2010 finale of The Hills, where a fake Hollywood backdrop was wheeled away to reveal they’d been filming in a studio lot, all the more radical). Today’s audiences are savvy and understand how content is made, so a little wink-nudge can go a long way: a producer bolting into frame in a moment of chaos; a Love Is Blind contestant putting in eye drops to fake tears; former Beverly Hills Housewife Denise Richards shouting the code word “Bravo, Bravo, fucking Bravo!” in an attempt to force the network to cut the scene.

But if the fourth wall has been slowly crumbling, it was bulldozed in this year’s The Real Housewives of Salt Lake City finale, which uncovered that new Housewife Monica Garcia was actually a fan – and handler of the Instagram troll account Reality Von (Tea)se – who had infiltrated the show. Cue an explosive finale: cinematic and darkly comedic, à la Big Little Lies; shocking, à la Succession; but also almost brain-breakingly meta. Then, the episode infiltrated the US government when a Democratic congressman quoted Heather Gay’s scene-stealing monologue – “Receipts! Proof! Timeline! Screenshots!” – in a committee meeting on Donald Trump’s business dealings. Does your head hurt yet

In the hours following the finale, social feeds buzzed with fan analysis. “Social media has made reality TV more of a lifestyle,” explains Pace. “You’re not just passively watching one season of a show and forgetting about it.” Instead, it’s an interactive, year-round soap opera bolstered by a cottage industry of podcasts and fan pages, plus a network of Reddit detectives who investigate every rumour and scandal like it’s true crime (in fairness, sometimes it is). “The whole world of engagement off the show has become as important as the show itself,” affirms Lindemann. It’s why more than 25,000 people make an annual pilgrimage to BravoCon, a convention akin to Disneyland for the reality world, where they mingle with fellow fans (Bravoholics) and stars (Bravolebrities).

"We get FILTHY and they get FILTHY RICH.”

The reality TV fandom is fervent, but they also hold their favourite shows to account. In 2021, The Bachelor audience rallied to have long-time host Chris Harrison removed after a racially insensitive interview. “I think it’s natural to try to hold this game accountable – like sports fans would – and hope that it can reach its highest ideals,” says Kultgen. He and Pace spent years closing every episode of Game of Roses with a DWABB count (Days Without a Black Bachelor) to highlight the dearth of diversity. In 2021, after 6860 days, the franchise instated its first Black bachelor, Matt James. Now the podcast does a DWAAB count (Days Without an Asian Bachelor), which sits at 7996 days at the time of publication.

Meanwhile, reports of manipulation and toxicity behind the scenes are rocking the reality industry at large. Last year Love Is Blind cast member Nick Thompson alleged Netflix producers withheld food and water during filming; he’s since launched a non-profit to provide mental health and legal support to reality cast members. Then there’s former Housewife and self-made millionaire Bethenny Frankel, whose (perhaps self interested) campaign advocates for the rights of reality stars, saying in a statement, “We have fed the machine ratings, ad dollars, catchphrases and content. We get filthy and they get filthy rich.”

Exploitation and bad behaviour are hardly unique to the reality industry, but they can still be hard to reconcile as a viewer. “[I watch for] the love of the game, but when the guilt starts to outweigh the pleasure, it’s like, am I contributing to this?” says Kultgen. “And that’s something we called out in our podcast very early on – being complicit and at least understanding that you are. But we’re all complicit in this entire thing. We all buy things off Amazon. So are we contributing to Jeff Bezos being a billionaire and building his spaceship shaped like a penis? We’re complicit in a lot of things that are bad for society. I feel like reality TV is just another one of those things.”

In many ways, the collective appetite for reality TV is entirely unremarkable. The genre represents what most of us are doing most of the time: sitting, scrolling and watching other people’s boring lives. Boring lives that are amplified, dramatised, edited and filtered for our viewing pleasure.

“In the future we’ll all be followed by credit card-sized drones that record our lives 24 hours a day, and whoever is the most interesting will have the most followers,” predicts Kultgen. Adds Pace, “And I can get an AI season where I’m the Bachelorette and I get to watch myself date my favourite celebrities.”

These projections aren’t outlandish when you consider that 26 years ago, The Truman Show felt far-fetched. But they’re enough to make the champagne-throwers, table-flippers and back-stabbers of Bravo feel kind of quaint. Could be reason enough to tune in now, before things really get stranger than fiction.

Barbie's world

From teenage Tumblr darling to young Hollywood star, Barbie Ferreira — who found fame through breakout roles in Euphoria and Nope — is only just hitting her stride. Courtney Thompson chats to Ferreira about how a weird theatre kid from Queens created the career of her dreams

Pleasure state

By now, most of us have heard the story: Australian advertising guru Richard Christiansen walked away from his New York agency during the pandemic and made one of the most celebrated tree changes of modern folklore, renovating a three-hectare property in LA, creating both a home and a brand – Flamingo Estate. Here, he talks us through his personal pursuit of the good life