Is everyone going to Greece but me?

Money dysmorphia is when we think we have more or less than we actually do. And in this age of overspending and oversharing, we’re all more affected than ever

Lunch at La Guérite beach club: $163. A martini at Loulou: $42. One night’s stay at Le Sirenuse: $4600. Posting about your Euro holiday on social media? Priceless.

If you’re not flitting off to the Mediterranean summer this year, you’ll probably be sitting on your couch watching people flit off to the Mediterranean summer. Champagne and olives in the airport lounge. Goyard bags and Dior Book Totes. Sun-soaked selfies featuring fizzy orange palomas and Cartier Love bracelets jangling on the wrist.

International travel used to be the reserve of the rich, who’d board planes and cruise ships bound for exotic locales while the rest of us chased boogie board waves in humble Australian seaside towns. Over the decades, though, with larger, more economical aircraft and the rise of budget airlines, holidaying abroad reached the masses. And when a global pandemic threatened to halt travel forever, our desire became insatiable. Enter the annual European summer sojourn, a concept and content moment normalised seemingly overnight. Today, the hostels, backpacks and £2 pints of old are swapped for business class airfares, luxury hotels and Michelin-star meals, all of which play out on social media like a wealth-porn reality show – because if you didn’t post it, were you even there? Meanwhile, those back home watch the highfalutin spectacle and wonder: How the hell can they afford that? And then: Why can’t I? Although if they can, surely I can, too… Let me put it on my credit card.

Am I rich? Or am I poor? This dissonance between one’s objective and subjective financial reality has been branded ‘money dysmorphia’, because in 2024 every phenomenon needs a pithy title. In a recent study by US finance firm Credit Karma, 43 per cent of generation Z and 41 per cent of millennials said they had a distorted sense of their finances. Whether it manifests in feeling like you have more or less than you actually do, money dysmorphia feels quintessentially now – though the term was coined by journalist Mona Chalabi in The Guardian in 2019, when she wrote about her scarcity mindset.

“I feel like I do not have money, even though I do,” wrote Chalabi. “I know objectively that I can go out to lunch, order a $17 burger and have plenty of money left over. But still, I’ll sit at the table stewing with anxiety over what I might need that money for someday. My warped reality comes from fears about the future – one where I might be back in a dingy bedsit, unable to pay bills or, even worse, relying on a man... I worry that if I actually let myself accept that I have money now, it will be even more of a shock if poverty does come.”

“Money feels so ABSTRACT; it’s easy to forget HOW MUCH you do or don’t have”

If Chalabi was concerned then, how’s she feeling now? In the past five years, we’ve lived through a life-altering pandemic and teetered on the edge of recession, all the while consumerism has been pumped with steroids. We’ve never been more obsessed with money: talking about it, stressing about it, pining for more. Our feeds are filled with stories of economic doom and gloom alongside recommendations to buy Maison Margiela’s $2080 Tabi boots and bottles of caviar-infused skincare. We read people’s money diaries and analyse their grocery bills, and take virtual tours of multimillion-dollar Brooklyn brownstones, Richter art collections and all. We try to create the Old Money aesthetic with preppy cardigans and tiny gold watches befitting someone who’s inherited lots of cash. It’s more tasteful and restrained than the garish Kardashian New Money aesthetic; though really, it’s still just an aesthetic, a kind of rich-person cosplay.

So, yes, we’re feeling all sorts of ways about money. Conversations with people traversing age brackets and income levels for this story highlighted a widespread sense of economic disconnect. “I stay at hotels that I never would have dreamt of staying at five years ago – and it’s not like I’m proportionately richer, it’s just become the norm,” shares one teacher. “My tap-happy behaviour is starting to scare me a little – the fact that you can shop straight from social media and don’t even have to enter your credit card details makes it all too easy. Money feels so abstract and it’s easy to forget how much you do or don’t have when you’re existing in this virtual bubble of luxury,” says a journalist. “I added up the cost of an influencer’s outfit the other day and it made me feel poor, until I remembered she probably got it all for free,” admits a banker. “I can’t afford bills.” This earnest admission from a 20-something in a sharehouse feels somewhat concerning, until it materialises that she’s actually talking about Bills, the Sydney establishment famed for its crispy corn fritters served with avocado salsa ($27).

Avocados are a seamless segue into the housing crisis and the demise of the great Australian dream. When it’s been drummed into you for a decade that you’ll never be able to afford a home, those Tabis might, in a twisted way, feel easier to justify. A more attainable dream. Such are the money mind games we play.

Perhaps we play these games because our economy is a riddle wrapped in an enigma. Scan news sources and the messaging flips so capriciously you wonder whether you should curl up in the foetal position or put your name down for a Birkin. “Who screwed millennials?” asks The Guardian; “The myth of the broke millennial,” rebuts The Atlantic. “Gen Z is being financially crippled by the cost of existing,” writes The Telegraph; “Generation Z is unprecedentedly rich,” contests The Economist.

What we do know is that money dysmorphia can lead to poor decisions, high anxiety and debt. HIFIs (High Income Financially Insecure, another pithy title) are the new subset of consumers who are objectively affluent, but struggle to keep up with housing and food costs because of recreational spending and lifestyle creep. “It’s become so easy to access money that isn’t yours, but you pay a premium for it,” says Molly Benjamin, founder of Ladies Finance Club. She points out that more than 40 per cent of 18- to 39-year-olds used Buy Now, Pay Later services in 2022, and that Australians racked up nearly $18 billion of credit card debt in February alone. That’s a lot of liability behind the smoke and mirrors.

"WOMEN are more comfortable talking about DEATH than money"

Perception is not reality, but the concept of wealth is deeply subjective. One person with $11,317 in savings is throwing dollar bills; another feels like they’re on the brink of destitution. “Our financial mindset is largely made up by the time we turn seven; it’s heavily influenced by how our parents behaved with money, and gender, too,” explains Benjamin. “Research shows that grandparents will buy dresses for their granddaughters and give their grandsons cash. Men have always controlled money and that knowledge has been passed down over generations, and it wasn’t until the 1970s that women could even open a credit card in Australia in their own name. It’s only a relatively short time period that women have had agency over their finances. And even now, women are more comfortable talking about death than money.”

So it would be safe to hypothesise that, studies pending, women are more prone to money dysmorphia than men? Yes, says Benjamin, but it’s also a choice. “It’s crazy to me that we go out and spend most of our time trying to make money, but little to no time learning how to understand or manage it.” For her, there’s no shame in trying to get rich (46 per cent of millennials in the Credit Karma study admitted they were obsessed with this pursuit), though today too many fixate instead on trying to look rich.

Money can’t buy happiness would be a trite adage to finish on, and perhaps a flawed one for anyone who’s woken up in an overwater Maldives villa or taken a shower on board a plane. Comparison is the thief of joy is equally cliché, but highly pertinent here. In this time of overspending and oversharing, most of us are struggling with what psychologists term ‘relative deprivation’, feeling disadvantaged based on comparison to someone else.

Maybe instead we should aspire to becoming rich in life. Driving a Ford Mustang from New Orleans to Nashville, top down, country music blaring. Watching the sunrise over a secluded Sri Lankan beach. Making life-affirming pasta al pomodoro in an Italian nonna’s kitchen, twirling it around your fork and relishing it slowly. All priceless.

The new normal

A Barbie breakout and star turn in Borderlands is all just par for the course for 16-year-old Ariana Greenblatt

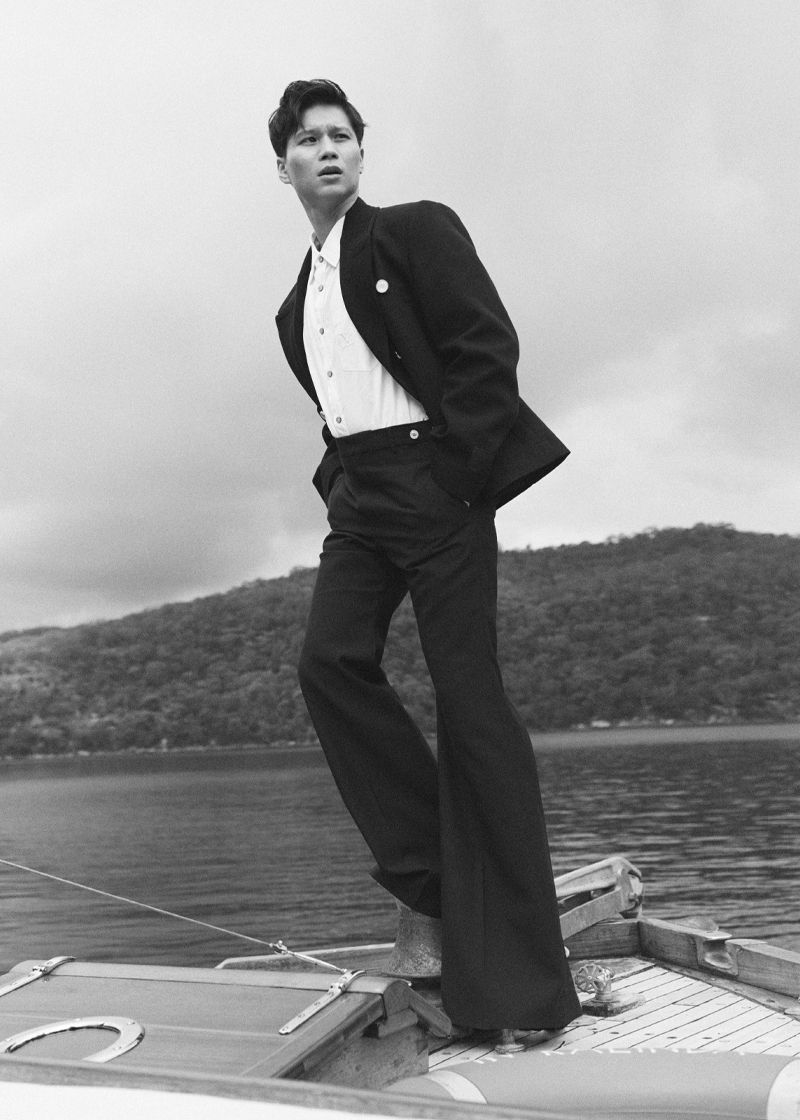

Hoa Xuande

From ABC to HBO, the Australian actor is fresh from his biggest project yet: top billing in the TV series The Sympathizer , alongside Robert Downey Jr.

Beauty world tour

An itinerary of the treatments, spas and buys worth travelling for (because sometimes a facial is just as iconic as a museum or monument)