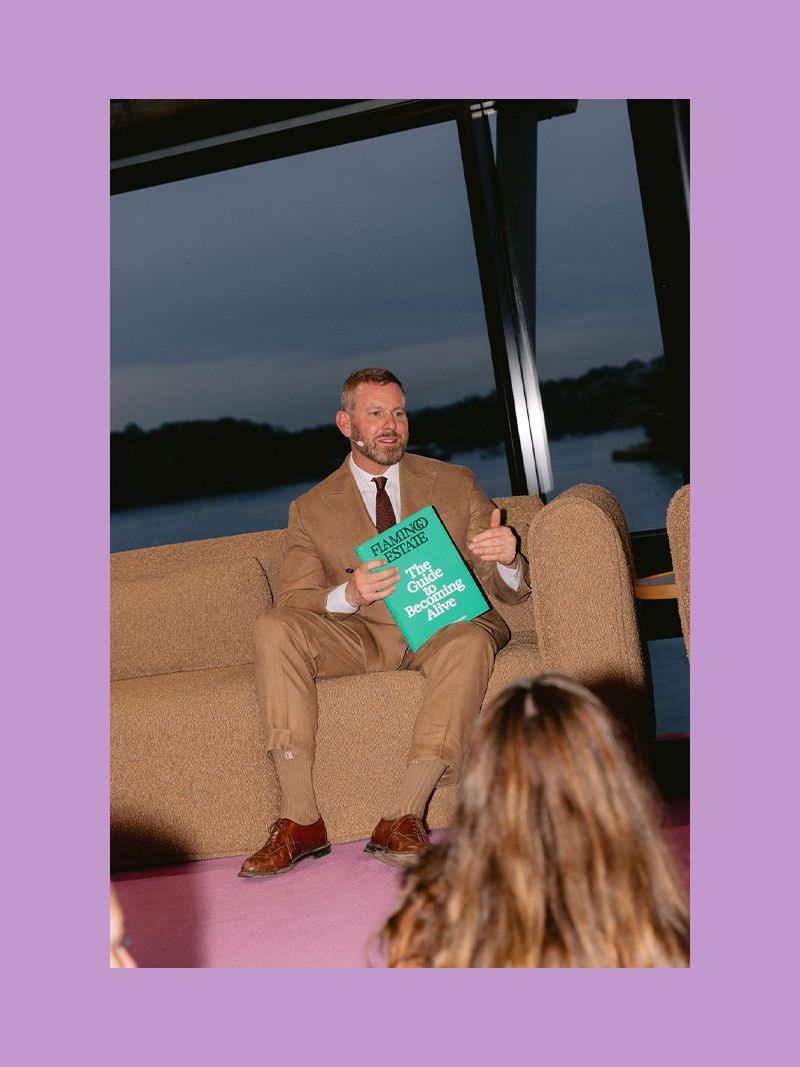

Living well with Richard Christiansen

In Flamingo Estate, he's built one of the most innovative and original brands on the planet. In his discussion with Editor-in-Chief Justine Cullen at the InStyle Beauty Summit, Christiansen talks about the importance of connection, radical inconsistency and ceremony.

PHOTOGRAPHY by CLAUDIA LOWE

INTERVIEW by JUSTINE CULLEN

To summarise the story of Richard Christiansen is a Heruclean task. But we’ll have a go. Christiansen grew up on a farm in Australia, but soon made his way to New York City, where he founded the agency, Chandelier Creative. At some point, and like many founders, feeling emotionally, physically depleted, he moved to LA, bought an old 1940s property called Flamingo Estate, restored it — and himself in the process — grew some plants, sold some vegetables, made some soaps… and has since grown Flamingo Estate the brand into one of the most innovative and original brands on the planet.

But as we learnt at the InStyle Beauty Summit, there’s much, much more to the Flamingo Estate story. In his discussion with InStyle Editor-in-Chief Justine Cullen, Christiansen takes us inside one of the most exciting companies shaping beauty and wellness today.

JUSTINE CULLEN: There's actually so much that could be said about the story of Richard Christiansen, but I don't want to waste any of my time with Richard tonight going over old ground. If you do want to know more, I highly recommend that you pick up his book, the Guide to Becoming Alive. It is such a very special book, I honestly don't feel like there's a person in the world who wouldn't feel in some way transformed after reading its pages. And I think that's something that I would say about the brand in general. It's a transformative brand. It’s original, it's purposeful, it's creative and authentic and to me it feels like a blueprint for how to live a richer, truer life. Welcome, Richard.

RICHARD CHRISTIANSEN: Thank you. That's so nice.

I want to speak a little bit about your world building to kick off, because I think when people talk about world building, yours is the very highest expression of that. It's visually completely unique, you combine nature and luxury and sexiness in a way that I don't think anyone has before. Is having a very distinctive original vision like this something you feel is particularly important today, given the proliferation of brands and dupe culture?

You know, for those of you that don't know, Flamingo’s my home and my partner Harvey’s home, and we started selling vegetables the first week of COVID for a farmer who was going to lose her farm, because her vegetables went to restaurants and all the restaurants were closed. And so originally, you know, we just started helping the farmer, and then one farm became two and then two became 128 farms. And you know, COVID was an amazing protective bubble, maybe for all of us, but for us especially because we were home just making, eating food. I had always worked in fashion and beauty, and I was so depleted, I was so tired, I was so sick of working with people I didn't respect. I also always thought I was fat. So I never ate anything and I didn't enjoy food. I wasn't feeling in any way alive. It was 20 years of just running a business. I was exhausted and sleep-walking through life. I wanted to be happy again. I wanted to feel sexy again. I wanted just to wake up! And so the original genesis of Flamingo was very selfish. It was just, how do we eat good food and how do we work with some farmers. And then maybe a year-and-a-half in, we had this wonderful farmer, Oliver, he said to me, help me sell my olive oil. And said, you know, I don't need more olive oil. But as he was walking out, he said, well, maybe we can make soap or candles from the olive oil. So that's how we accidentally got into the beauty industry.

It wasn't always in the back of your head somewhere? You’d worked with other people’s brands for so long.

No, in fact, because I've worked with so many brands for so long, it was the opposite. I was so allergic to marketing pitches, so allergic to the soundbite. I was really resisting. I said then and I say now, don't come to us for innovation. What we're doing is not being innovative. We just want to make everyday stuff that we need to use and do it really well. And the growth was astounding. 150 products in the first year and a half, different SKUs. It was just crazy. Farmers would come and say, I've got seven acres of sage, I've got 50 acres of lavender, I've got this, that. When you start a brand, you know, many people will say, oh, I know I'm gonna start this thing, let me go find the ingredients. We were the total opposite. We had these farmers coming to us and saying, I've got 28 acres of something, what can you make from that? So it was all sort of top down.

Is it still that way, still led by what's available to you and what you want to make and use? Or do you have to think more about the end-use now, the customer?

Yeah, it is that way still. I think the business took a real turn when I met Jo [Horgan, founder of MECCA] and Marita [Burke, MECCA’s Head of Marketing & Brands] and they came to see me in Los Angeles and said, there's this sort of collision of nutrition, wellness, beauty — we see it in Australia and no one can really deliver on that because people don't make stuff that way anymore. But, because we were just sourcing directly from farms, actually maybe we could deliver on it. And that sort of took us to a place where we went from the kids table to the adults table in a way, just because we had to think about packaging and margins and all that stuff growing brands need to think about. And obviously in America we’re a huge business now. But you know, it's still a home. We live there, we just make the stuff that we need to use every day. And it's remarkably uncomplicated, you know. We're really lucky. We're very grateful. We've had an amazing, amazing, amazing adventure. And it's been four years and it's been crazy.

You talk a lot about radical inconsistency. What does that mean to you? How do you define that and what does it mean in a beauty context?

I get really fatigued with the beauty industry. If something is harvested, fresh from the farm and bottled that way, you would expect it to maybe smell different. Different seasons mean more rain, more sunshine, there's more wind. If it's made by real people on a farm and not in a test tube, it's going to be different. We expect it from olive oil, we expect it from wine — so why don't we expect it from hand soap if it's made really well? And so I love the idea that our products should always be really, really good, but they should always be different. If it comes from our home, it should be great, but it doesn't have to be the same. I really love that idea and it's harder now that we've scaled, but for stuff that we do seasonally, we have so much fun and we really continue to keep thinking about how we can get more and more inconsistent. We need surprise, it's so boring to think you’ve got to look the same for 10 years.

Do you apply radical inconsistency to the rest of your life? Or is it just for the brand?

I think working in a corporate job for 20 years, you know, I'm just like, I'm hungry for surprise and I'm hungry for pleasure. It sounds cheesy, but I want to eat everything. I want to drink everything. I want to taste everything, smell everything. There's nothing sexy about restriction. I feel like what we need is to deeply taste things and smell things and, and just be in love with our senses.

Your social and email feels very personal from you. Is that purposeful?

I remember going to this conference a couple years ago and there was this distinguished person in the industry at the check-in desk. And someone who was working at that company, came up with a very young new hire. It's like, oh, this is so and so, she's gonna be running our social media. I thought, oh my God, why are you going to let the least qualified person in the business be in charge of the biggest window of your brand? You should be writing your own social media, you’re the founder of this company! Bobbi Brown's been really good to us and with her brand, it's like, she's in it, she's writing it, she's doing all of it. I really, really feel it when someone's really there. You don't out-source that. To me that's very important. Very.

You’re not wanting for inspiration at Flamingo Estate. But how do you take something from being just an idea or a feeling into a tangible product? What is that process like?

It's funny because now that we've been working on investment, it's very hard to define ourselves. Are we a food brand? Are we a beauty brand? We get a lot of criticism from the investors about that. Like, pick a lane, what's the roadmap we're following? We don't really have one. We still sell fresh produce, we still sell flowers, we still sell lots of food. We still sell beauty products. But I think that the red thread is that we’re an ingredients brand. For example, Jalama Canyon Ranch is an amazing, biodynamic living laboratory of thousands of acres of black sage, which is very hard to find, fresh like that. They'll come and say, we've got this amazing harvest, let's do something. So let's make a soap, it’s really started in the conversations with those people.

How many people are part of Flamingo Estate now?

We’re small. We're about 40 people in the main office and we still do all of our fulfilment, everything. Everything's in the building, we have a kitchen in the building. We try really hard to hold onto that, really tightly. Scale is the enemy of intimacy, and we’re all about that intimacy as a brand — it’s about having a shower, it's about having a bath, it’s about having a meal with someone you love. Scale is the enemy of that feeling. I've always felt that. You know, at the agency, people would come to us from brands — big, big brands and small brands, all sorts of brands. And really, at the end of the day, they all had the same question, and the question was always, how can you help us act small again? We got too big to be vulnerable. We got too big to be funny. We got too big to be silly. We got too big to be something. Help us not be small, but to act small. And so if I learned anything from my old life, it was remembering that. And that's really like, so core to what we do. Harvey designs, all the packaging, all the design work, everything. We had a store in the Hamptons this summer with all the in-house packaging and I joke that it was a museum to all of our arguments because it was all the stuff that we talked about endlessly over the kitchen table.

You’re really living inside your brand. Are you ever able to turn it off?

HARVEY, FROM OFF-STAGE: No!

[Laughs] Do you want to?

We love it. We really love it. We're having a great time. It's fun.

How do you grapple with this idea of scale and investment and keeping that intimacy? Are you just fiercely protective of it so there's limitations as to how far you would take it, or as you grow are you finding yourself more open to different ideas?

I don't know. I think anyone can have an idea to start a brand. And we were very lucky, in some ways. But as many people in this room know, the work is in scaling a brand and we had 160 meetings before someone gave us any investment money. I thought we'd get money straight away, we were a popping brand, we were selling well. No. It was so hard for people to understand the bigger vision. The next book I write really should be about the need for radical inconsistency in the investment community because, God, it was so hard. I remember this one meeting, someone said, what's the margin on your hand soap? So I said the number, which is a very respectable number and the person across the table, she said, oh, come back when you’re at 95% margin. And I was like, we can't be at 95% margin. We can't because we’d have to get commodity ingredients from overseas. You know, when you start to squeeze everyone on the margin, the farmers get fucked. And that's why we're doing it, because we want to work with people like my mum and dad, who are farmers, we’re going to pay them really well. And we really want people who help climate change and treat the soil well and treat people well and treat people fairly. If you take on someone else's money, you know, you're going to have this headwind about margins, which is the conversation we've had over and over and over again. I think there's a way to scale a big global beauty business and pay people fairly and do it really well. And one of the reasons I'm now so hungry to scale this brand, it's not because I'm ready — I’m much happier actually just at home with my dogs — but it’s because no one's done that before and I'd like to do it to say, it can be done, you can do it that way. And we can give back and give up, we can take the money we earned and do something with it and we can put our resources into it around the world. I'm very passionate about that stuff.

Did you even have 160 people whose money you would have been comfortable to take? Were there that many investors whose values matched yours?

It took me a while. I had never asked anyone for money. I was the sort of person that never even checked their balance at the ATM machine. Like, I'm not a money person. And so getting into that community was new for me. But we've been lucky. It took a long time. It took 160 meetings, but we had some fun. We went to Paris, we went to see LVMH. They were like, oh, you guys are really interesting. I walked in, I've known some of the people there from my old life and they were like, what are you doing here? I said, oh, I've got this brand. And this guy, he didn't give us any money, but he said, I think you're doing the one thing LVMH brands want to do, but I don't think you're doing it very well and I don't think you even know you're doing it. And I said, what is that? And he said, you're scaling scarcity. He said, there's only so much champagne you can make, the region is not growing, which is why we're doubling down on the cost of it in the bottle and scaling the idea of scarcity, which is luxury, right? And so he was like, you know, there's only so much lavender you guys can make. There's only so much sage you can harvest if you really are doing that with the farmers. And that was my one takeaway from that meeting. I remember very clearly, I came back to the office and I said, we need to start talking about the preciousness of all this stuff, that we make 400 bottles and we're not making anymore. We've got one harvest and it's only here for three months. And so that changes a little bit, it changes the messaging of the brand, which really resonated.

That comes through so clearly. You make marigold feel like a limited edition CELINE drop. What excites you about this industry in general and what excites you less? You mentioned convenience to me earlier.

We write about this in the book. There's a great interview with this guy, David Leon, who talks about technology, the promise of convenience, that technology would allow us more time to do the things that we really love, like taking a hot bath. But what it did though, was it just made us scroll endlessly.

Take the phone into the bath.

Totally. And so in that way, convenience is also the enemy of intimacy. And the one thing that I know with my full heart, is that technology — especially that promise of convenience — it kills ceremony. And what we need as humans is ceremony. We need to set a table. We need to spend time with our families. We need to cook dinner for someone, not shove it in the microwave and sit in front of a television. The sort of timeless things that we know from our grandparents. And I think that same thing applies to the beauty industry, just in terms of a return to ceremony and personal rituals. We talked on the phone the other day, and you said people come and say, oh, I made the one product I needed because I could never find it…

"One of the reasons I'm now so HUNGRY to scale Flamingo Estate, it's not because I'm ready — I’m much happier actually just at home with my dogs — but it’s because no one's done that before and I'd like to do it to say, IT CAN BE DONE, you can do it that way."

Yes, and I’m like, where are you looking? There’s so much of everything.

Yeah. And not just in the beauty space. I get really sick of the challenger brands and the disruptive brands, because sometimes the everyday things, the really honest things, sometimes they’re just the best ones. And that excites me. A return to that really excites me. There's an interview in this book with Alice Waters, she’s the original farm-to-table chef in America. And Alice says, what you put in your mouth is what you put into the world. And I think the same applies to the media industry as well. And she has a pretty nice conversation about how in the fifties, when fast food started, processed food, when the wind hit the sails of that, that we started to digest the values of that food system. Faster is better, cheaper is better, more is better. With no appreciation for the cost of that, the human cost of it and the downstream cost of who's making that stuff, harvesting that stuff. I think there's something really important about that, that we digested those values. And I see it in this industry as well a little bit. She says it's very selfish and it's very irresponsible not to understand where the things you're eating are coming from. And the same is true of what's on your bathroom cabinet.

I'm going out on a tangent, but we talked yesterday about the US election, which was, I think, in many ways, about people not doing the homework. I think the President-Elect is sort of this person you might like if you're seeking answers, but not asking questions. Because we've been spoon fed a lot of stuff that we're getting and we're not questioning that. And I think there's a link to that and the way we just consume products as well and the way we consume media, which encourages me to question more, really asking questions about everything we've got and everything we buy. I think that’s something we all need to do to be able to see change.

If you could give one simple piece of advice to the people in this room who might be starting a brand or growing a brand, what would it be?

Oh, wow. Don’t use AI? I mean, honestly there’s no shortcuts. The people that I've found that I've loved, people I've met, they’re just doing the groundwork. There's no shortcut. Jo Horgan, the founder of MECCA, who has been such a big supporter of us, she says, if you don't fail, if you don’t fall on your ass enough, you don't have big enough dreams, which I think is a really good one. And one of our favourites Jo said was, you've got to surround yourself with cup fillers, not cup drillers, in terms of the people around you, which means on your team as well.

There's a chapter in my book called ‘Cut Your Roses’. Because anyone with a garden knows you’ve got to take the scissors to your roses every year for them to come back really strong. You've got to, like, hack the roses. And you have to do the same with your life and with your business. You've got to take the scissors to the stuff that's not working and the people who are not working, the stuff that doesn't make you happy. You’ve got to get rid of all of it and come right back stronger. It's one of the simple lessons from the garden. So maybe that's my advice, get your scissors out.

Inside the inaugural InStyle Beauty Summit

Presented by Zeekr.

Celeste Barber wants you to feel seen and heard

An Instagram sensation, actor, stand-up star, national treasure — and, now, beauty founder with her makeup brand, Booie. In her conversation at the InStyle Beauty Summit, she discusses creating something for the people who were left behind.

Inside the minds powering the beauty industry

In their panel discussion at the InStyle Beauty Summit, four of the leading minds shaping beauty today discuss the future.